The Cauvery Water Dispute

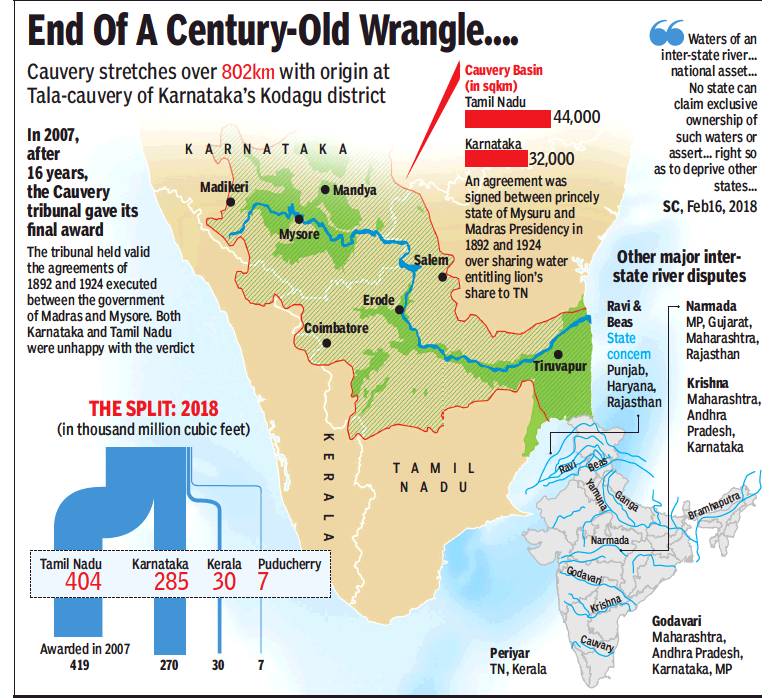

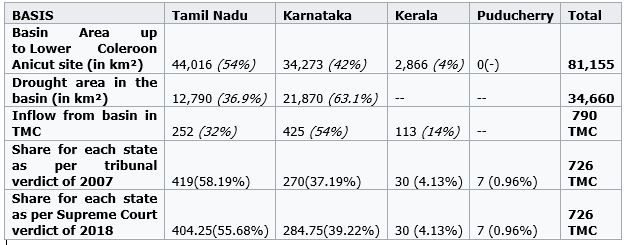

The sharing of waters of the Cauvery River (also spelled as Kaveri) has been the source of a serious conflict between the two states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The genesis of this conflict rests in two agreements in 1892 and 1924 between the erstwhile Madras Presidency and Kingdom of Mysore. The 802 kilometres (498 mi) Cauvery river has 44,000 km2 basin area in Tamil Nadu and 32,000 km2 basin area in Karnataka. The inflow from Karnataka is 425 TMC ft whereas that from Tamil Nadu is 252 TMC ft

The sharing of waters of the Cauvery River (also spelled as Kaveri) has been the source of a serious conflict between the two states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The genesis of this conflict rests in two agreements in 1892 and 1924 between the erstwhile Madras Presidency and Kingdom of Mysore. The 802 kilometres (498 mi) Cauvery river has 44,000 km2 basin area in Tamil Nadu and 32,000 km2 basin area in Karnataka. The inflow from Karnataka is 425 TMC ft whereas that from Tamil Nadu is 252 TMC ft

Based on inflow Karnataka is demanding its due share of water from the river. It states that the pre-independence agreements are invalid and are skewed heavily in the favour of the Madras Presidency, and has demanded a renegotiated settlement based on "equitable sharing of the waters". Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, pleads that it has already developed almost 3,000,000 acres (12,000 km2) of land and as a result has come to depend very heavily on the existing pattern of usage. Any change in this pattern, it says, will adversely affect the livelihood of millions of farmers in the state.

Decades of negotiations between the parties bore no fruit. The Government of India then constituted a tribunal in 1990 to look into the matter. After hearing arguments of all the parties involved for the next 16 years, the tribunal delivered its final verdict on 5 February 2007. In its verdict, the tribunal allocated 419 TMC of water annually to Tamil Nadu and 270 TMC to Karnataka; 30 TMC of Cauvery river water to Kerala and 7 TMC to Puducherry. Karnataka and Tamil Nadu being the major shareholders, Karnataka was ordered to release 192 TMC of water to Tamil Nadu in a normal year from June to May. The dispute however, did not end there, as all four states decided to file review petitions seeking clarifications and possible renegotiation of the order.

In a judgment aimed at putting an end to a water dispute that has lasted for over a century, the Supreme Court on Friday reworked the share of Cauvery water to be made available to Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. The order amends the 2007 decision of the Cauvery River Water Tribunal by reducing the amount of water that Tamil Nadu is due, passing that share to Karnataka. But the judgment also raises a number of questions, from the method with which the court revised the shares to the question of whether states will actually comply with the orders in distress years.

First the details of the judgment itself. Amending the 2007 final award of the Cauvery river water tribunal, the Supreme Court reduced Tamil Nadu’s share of the water in the Cauvery basin by 14.75 thousand million cubic feet or TMC and fixed it at 404.25 TMC. Karnataka’s share increased by the same amount and went up to 284.75 TMC. Kerala and Puducherry will continue to get 30 and 7 TMC respectively, with 10 TMC allocated for environment protection.

According to the tribunal, the total amount of water available from the Cauvery, based on 50% dependability at the Lower Coleroon Anicut site in Tamil Nadu, was 740 TMC. This was the figure used to calculate the water to be shared.

Since the Cauvery flows from Karnataka into Tamil Nadu, the judgment ordered the former to release 177.25 TMC to Tamil Nadu annually, made available at the interstate border of Billigudi. This is a reduction from 192 TMC that the Tribunal had allotted Tamil Nadu.

Bengaluru’s status

The Supreme Court has recognised the special status of Bengaluru in the whole equation. The tribunal in its order in 2007 said only 1/3rd of Bengaluru fell in the Cauvery basin. The population projection for 2011 for this 1/3rd was obtained and water was allocated proportionately. It also presumed that 50% of the drinking water will come from groundwater sources.

Thus, while the total need was put at 17.22 TMC, 50% of this was discounted as it would be met with groundwater. Of the other 50%, which worked out to approximately 8.75 TMC, the consumptive use of the 1/3rd area was fixed at 1.75 TMC or 20% of 8.75.

The Supreme Court pointed out that there was no basis for arriving at the figure of 17.22 TMC and the assumption of 50% being met with groundwater was flawed. Further, given that drinking water was the most important of all uses of water required for sustaining human and animal life, the court was not ready to accept that only 1/3rd of the city should benefit from Cauvery water. The geographical limitation of the basin was overlooked with Bengaluru being a special case with phenomenal growth over the last few decades.

The court said, “We think so since the city of Bengaluru cannot be segregated having an extricable composition and integrated whole for the purposes of the requirements of its inhabitants, more particularly when the same relates to allocation of water for domestic purposes to meet their daily errands. It will be inconceivable to have an artificial boundary and deny the population the primary need of drinking water.”

Therefore, it increased the Bengaluru’s share by 4.75 TMC. This meant the two components–groundwater and Bengaluru’s share – together took away 14.75 TMC from Tamil Nadu.

Distress sharing

Having reworked the water-sharing formula, the Supreme Court has adopted major parts of the tribunal award, including the timetable of water release.

This also includes the distress-sharing formula. The tribunal in 2007 said in years when water flow is less than the 740 TMC, the Cauvery waters will have to be shared proportionately.

The distress of decreased water flow will have to be shared by the states as per the original water sharing formula, that is the manner in which the tribunal apportioned the 740 TMC. The guidelines state:

“The Regulation Committee shall keep a watch on the actual performance of the monsoon during each ten daily interval and report position to the Board indicating therein the extent of variation from the normal. The Board on receipt of such information will consider any change in the release ordered by them earlier. Similar exercise will continue as the monsoon progresses during the succeeding months till the end of the water year i.e. 31st May of every year.”

Here is the problem in the scheme. Agriculture in the Cauvery basin depends on a combination of river water and rain water. When the monsoon fails, it is a double whammy: the storage in the dams reduce and the rains diminish. This means, the stress on the available Cauvery water would increase.

Karnataka over the years has compensated for deficient monsoon by exploiting Cauvery water without providing Tamil Nadu its share. Its argument is that the prospect of sharing the river water doesn’t exist in a situation where even its drinking water demand is not adequately met. Therefore, Karnataka has refused to honour the very concept of proportional sharing during a distress year. Any attempt to force the state to share water in a deficient year has resulted in political stubbornness to the extent of violating Supreme Court orders and riots and violence on the ground.

Karnataka over the years has compensated for deficient monsoon by exploiting Cauvery water without providing Tamil Nadu its share. Its argument is that the prospect of sharing the river water doesn’t exist in a situation where even its drinking water demand is not adequately met. Therefore, Karnataka has refused to honour the very concept of proportional sharing during a distress year. Any attempt to force the state to share water in a deficient year has resulted in political stubbornness to the extent of violating Supreme Court orders and riots and violence on the ground.

The Supreme Court order reiterated the tribunal’s scheme of distress sharing, which in a way discounts reality and politics of river water disputes. The assumption here is that sense will prevail and that the state would adhere to the formula by reducing its water use in a difficult year. This is why the court made it clear that no one state has absolute rights over Cauvery.

While the emphasis on judicial use of water is commendable, it hardly solves the problem of distress sharing. In essence, the battle over Cauvery could witness the same cycle of events that has taken place in the past decades given the impracticality of this formula. The problem becomes even more difficult when one takes into account the party politics of Karnataka, which is now ruled alternatively by the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Congress. Given that the Centre will play a crucial role in the Cauvery Management Board, the commitment to the Supreme Court order could very well depend on the political weather rather than legal obligations.